Robert F. Grover, MD, PhD (1924-2021) passed peacefully in his sleep. His long career began with his service in the European theatre during World War II. One of his posts was at a radio relay station atop the Zugspitze at 10,000 feet in the Alps. It was there that Dr. Grover fell in love with the jagged peaks and massive glaciers of the high mountains. After the war, he moved to Denver to be near high mountains. It was there that he attended the University of Colorado Medical School where he received his M.D. and PhD. degrees. Following post-graduate study, he was appointed director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at the Medical School.

As with so many of the post-war generation of scientists, Dr. Grover established his own unique path in research. From the beginning, he was intrigued by the number of patients with pulmonary hypertension who lived at high altitude. This cohort, frequently coming from Leadville, CO (3,000 m), had lived for two generations in that hypoxic environment. To extend his work to subjects who had lived for many generations at significantly higher altitudes, Dr. Grover made a number of trips to South America to investigate exercise and ventilatory control in Quechua Indians of the Peruvian Andes, Aymara Indians of the Bolivian Andes, and later Sherpas of the Himalayas. As his career flourished, his research expanded to studies of the effects of high-altitude on control of breathing, and the regulation of cardiac output.

altitudes, Dr. Grover made a number of trips to South America to investigate exercise and ventilatory control in Quechua Indians of the Peruvian Andes, Aymara Indians of the Bolivian Andes, and later Sherpas of the Himalayas. As his career flourished, his research expanded to studies of the effects of high-altitude on control of breathing, and the regulation of cardiac output.

Over time, Dr. Grover's early career interest in the cardiopulmonary adaptations to hypoxia became the overriding theme for a growing group of university scientists. Under Dr. Grover’s direction the Cardiovascular Pulmonary Research Laboratory (CVP) was formed in 1965.

As the reputation of the CVP lab grew, so did the group of outstanding research fellows. Dr. Grover’s reputation drew many young scientists from all over the world. One mark of the success of the CVP was that so many fellows stayed in academia (63 percent when Dr. Grover retired) with many having distinguished careers of their own. With that group and those that followed and in turn their own MDs and PhDs fellows, the Grover scientific tree continued to grow exponentially. The key for such an outstanding training record lies primarily in Dr. Grover's belief that the enthusiasm and brilliance which young minds bring to research would develop if given thoughtful encouragement. But his primary talents, and those which caused the CVP laboratory to be built into one of national and international prominence, were his abilities to develop an extensive network of collaboration both inside and outside of the laboratory. It is not an overstatement to say that he was not only respected for his judgement, but that he was loved for the interest he showed in everyone: the faculty, fellows, technicians, secretaries, and the maintenance staff.

Dr. Grover set a standard that the daily morning conferences by the research fellows and faculty were required to be clear enough so that the entire laboratory could understand even the most complicated findings.  Clarity of presentation was deemed a manifestation of clarity of thought. The combination of these qualities built a laboratory where people worked together to make a team much greater than the sum of its individuals. One important marker of success of a laboratory is the ability to carry on after its leader retires, rather than the usual path to collapse after the founder is gone. The remarkable foundation that Dr. Grover laid has succeeded through generations of superb leaders: this year the CVP NIH Training Grant has been refunded for its fiftieth year and the CVP NIH Program Project Grant has been refunded for its fifty-fifth year.

Clarity of presentation was deemed a manifestation of clarity of thought. The combination of these qualities built a laboratory where people worked together to make a team much greater than the sum of its individuals. One important marker of success of a laboratory is the ability to carry on after its leader retires, rather than the usual path to collapse after the founder is gone. The remarkable foundation that Dr. Grover laid has succeeded through generations of superb leaders: this year the CVP NIH Training Grant has been refunded for its fiftieth year and the CVP NIH Program Project Grant has been refunded for its fifty-fifth year.

During Dr. Grover’s career he gained international recognition for his research and received numerous awards. Important recognition came with the establishment of the Grover Prize, an endowed Prize named in his honor. The award was designed to honor senior scientists whose distinguished work led to advances in understanding the control of the pulmonary circulation. In 1995, Dr. Grover received the Edward Livingston Trudeau Medal given to an individual with lifelong major contributions to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of lung disease through leadership in research and education.

An informal family atmosphere developed in the CVP laboratory which made it fun to work hard even on weekends. Office doors were never closed during working hours, which readily facilitated interaction among faculty, fellows, and technicians. Everyone had a master key for after-hours work. Imagination was not confined to science—the place was a magnet for practical jokes. These pranksters included fellows and technicians and were encouraged by some of the less mature faculty. Even the famous Dr. Grover was not immune. He was simply known as Grover after the Sesame Street character Grover, a doubly appropriate nickname as they both loved to travel. Dr. Grover’s photograph in the conference room was replaced by a photograph of Grover from Sesame Street. So much for formality.

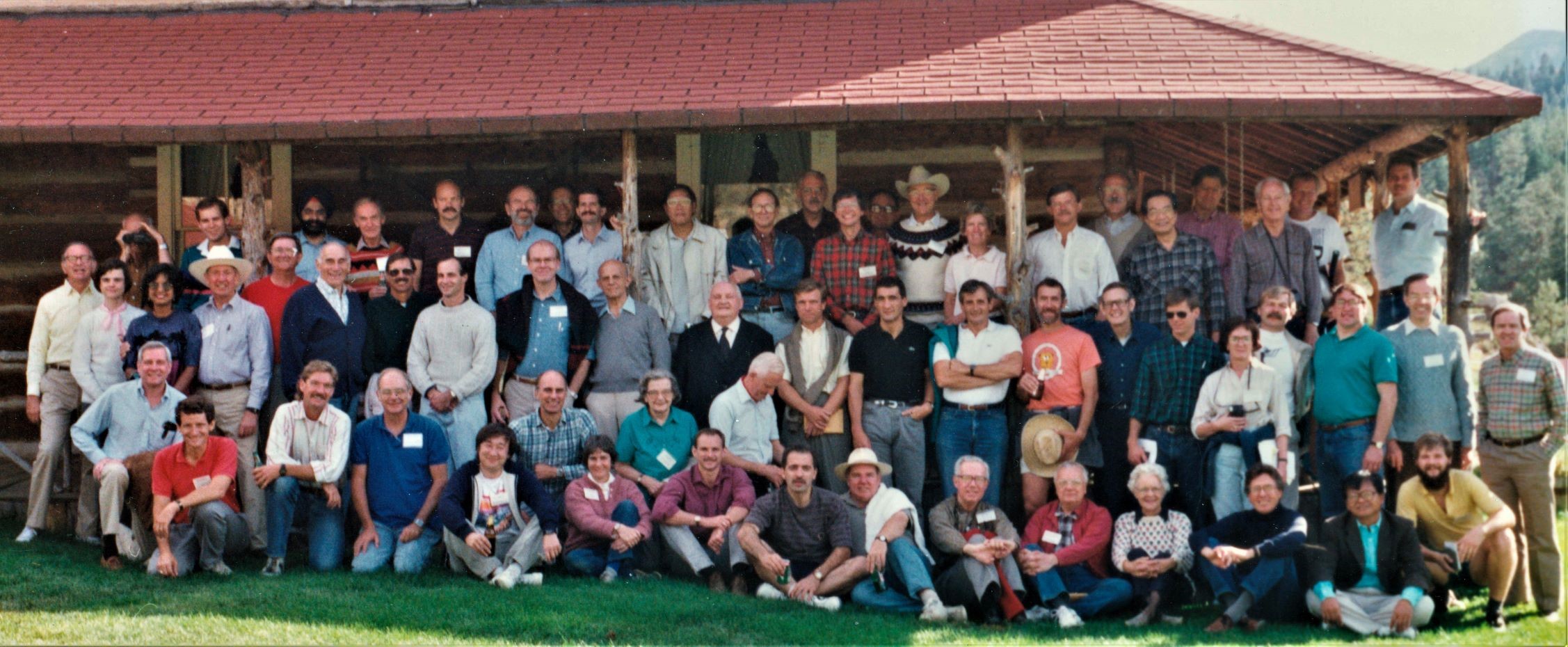

The respect and gratitude which the laboratory faculty felt toward him led to the establishment in 1984 of the Grover Conference on the Pulmonary Circulation. The conference continues to meet every second year at an isolated Colorado ranch. The next conference will be the nineteenth meeting. The conference is designed to mix senior and junior investigators of the pulmonary circulation with the best of international scientists, who specialize in fields related to the particular topic of each conference. These conferences have proven to be of the highest scientific quality and to instill the excitement of collaborative inquiry and motivation to persevere into the next generation.

Dr. Grover’s dream has no end in sight.